July marks nearly three decades since President George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act into law, making it the nation's first comprehensive civil rights legislation designed to protect people with physical and cognitive disabilities.

All this month, WYSO is bringing you stories of Ohioans living with disabilities. It’s a series we’re calling Just Ask: Talking About Disability.

The series grew out of a training WYSO conducted this spring with four Miami Valley disability advocacy groups. For six weeks, producers April Laissle and Anna Lurie collaborated with people with disabilities to create radio stories.

Participants told us what topics were most important to them, and the series kicks off with a look at how the Americans with Disabilities Act has - and has not - improved conditions for many people with physical disabilities in the Dayton area.

Applause punctuated the outdoor signing ceremony, where President George H.W. Bush told the crowd the Americans with Disabilities Act would for the first time in history guarantee independence, freedom of choice and new opportunities for people with disabilities.

“And now I sign legislation, which takes a sledgehammer to another wall, one which has for too many generations separated Americans with disabilities from the freedom they could glimpse, but not grasp. And once again we rejoice as this barrier falls, for claiming together we will not accept, we will not excuse, we will not tolerate discrimination in America.”

The Americans with Disabilities Act took effect in 1990. The landmark law built upon previous legislation, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, which banned discrimination in programs that receive federal funding.

The ADA expanded these protections to bar discrimination in the public and private sectors. The ADA prohibited employment discrimination. It promised people with disabilities equal access to public spaces and private businesses, such as restaurants, stores, hotels and offices. It promised equal access to telephone service and transportation.

And over time the law transformed America’s built environment in key ways. Today, design elements such as wheelchair ramps, accessible bathrooms and parking spaces are ubiquitous in most areas of the country.

It wasn’t always this way, says veteran Ohio disability rights advocate Susan Willis, who recalls how different things were before the passage of the ADA. When the law took effect, she walked with crutches.

"A lot of things are better. I remember attending Ohio State University when there was no ADA and traversing that campus for me was terribly difficult. There were steps at every building," she says.

Now, Willis uses a motorized wheelchair. She says despite significant progress in improving accessibility for many people with physical disabilities, violations of the ADA are stubbornly pervasive.

“Granted, I will give the public a lot of credit for helping us get what we've got, but it needs to do a lot more. The cities, the communities, they have to decide that this is important and that we're going to do it,” she says. "There was a time after the ADA went into effect, they were given an amount of time to get things fixed. Well, that time limit has come and gone."

More than 16 percent of Montgomery County residents live with a disability, according to an analysis by the National Center for Family and Demographic Research at Bowling Green State University.

Statewide, between 2011 and 2015, an estimated 1,545,626 Ohioans lived with a disability, according to data from the 2015 American Community Survey. That's more than 14 percent of the state's civilian, non-institutionalized population over age 5.

Under the ADA, people can bring lawsuits or file complaints with eight federal agencies, including the Department of Justice and the Department of Transportation. But there’s a growing backlog. Change is slow.

“Because the ADA is a civil rights law. You don't see cruisers around that have civil rights police written on it," says Greg Kramer, assistant director of the Dayton Access Center for Independent Living.

Kramer says the burden of ADA enforcement falls largely on the public.

“So, what do you do? If you can point out that they're in violation of a federal law and they don't do anything, what is your recourse to get them to change? And the only recourse is to file a complaint,” he says.

Take parking, for example. Kramer uses a wheelchair and drives a full-size accessible van, and says people without disabilities often park in accessible spaces thinking they won’t get caught. He’s learned to leave extra time when running errands around town.

“I might go to a grocery store and all the accessible parking is taken. So, I mean, there's been times I've had to drive around the parking lot a couple of times and wait until somebody leaves,” he says.

Read more about ADA regulations.

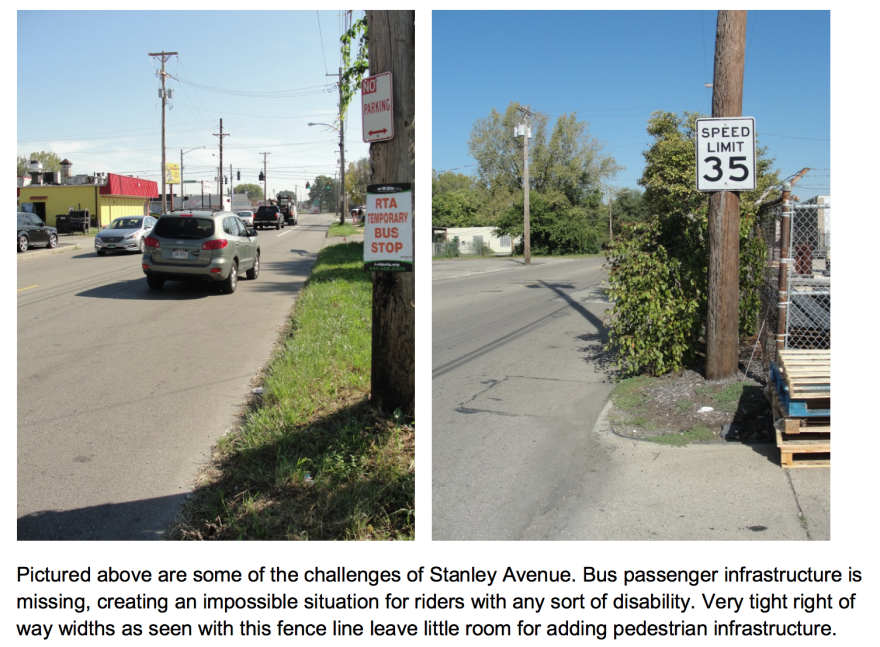

Trucks rumble past outside the Access Center, in this mostly industrial area near Interstate 75. The main drag, Stanley Avenue, is curved, offering limited visibility for drivers.

A recent survey by the Miami Valley Regional Planning Commission found Stanley Avenue in the McCook Field neighborhood was “not safe” for people with wheelchairs or strollers.

There are few crosswalks or sidewalks available for people coming to and from bus stops, Kramer says.

“Now, if you go down on Stanley Avenue, on the right side there is sidewalks but then they just end – not at a curb cut. It ends at the end of a business."

Incomplete sidewalks force people with wheelchairs or walkers out into traffic.

Or onto the grass. And grass, says Access Center Board Vice Chair Art Schlesinger, who uses a motorized wheelchair, is no substitute for sidewalks.

He points to a nearby grassy patch where a sidewalk abruptly ends about a block from the nearest transit stop. The grass is long. The ground is uneven.

“This wheelchair is powerful enough that I could probably roll through the grass," he says, "but God forbid that it's muddy and I get stuck in the mud, and I've had that happen to me.”

More education is needed to help lawmakers, home and business owners understand the importance of sidewalks, Kramer says. But it’s not always easy to convince small business owners to install new sidewalks on private property.

“Because you are encroaching on business property," Kramer says. "So, the business would have to give permission, they can charge you. How can you put that sidewalk in?”

Sidewalk maintenance is also critical to people with physical disabilities, he says. It's something many people without physical disabilities may not even notice.

“When you have sidewalks and there's a tree next to the sidewalk, that root might raise that sidewalk up an inch. For somebody who uses a wheelchair, that inch is a wall to us. There's no way to get over it.”

In the United States, aging is known to be a big risk factor for disability. Research shows the older you get, the more likely you are to have a disability. Kramer has relied on a wheelchair for most of his life.

"I got injured in 1977, when I was 15. Fifteen-year-old boys, we think we're invincible – and I was at a friend's house just messing around, and I attempted to dive into their pool and I broke my neck. So my life changed in a second."

Roughly 40 million Americans are over age 65. The number of people age 85 or older is projected to more than triple by 2050, National Institute on Aging research finds.

As the population ages, Kramer hopes more Americans will become sensitized to accessibility issues.

“We are living longer. Whether it's your vision, your hearing or your mobility, at one point one or all of them might be affected because you age into it,” he says.

Ultimately, making public and private spaces more walkable and disability friendly will likely make getting around easier for everyone, young and old.

"We're trying to make our communities as livable for people with disabilities as those who don't have any. And it's also becoming very important for our senior citizens. We're getting more and more people aging who, they may not identify with a disability, but they may have arthritis or heart disease or things like that, and these ADA rules are equally important to them as they are to a person labeled with a disability," Willis says.

_