In the late 1960s, black students on college campuses around the country were at the vanguard of protest to bring about change in the world around them. While there is an extensive record of student views of these activities, we rarely hear the perspectives of faculty and administrators who worked at these campuses. Community Voices producer Kevin McGruder looks at the challenges facing faculty and administrators during times of student unrest on the campus of Wilberforce University in the late 1960s.

"I remember going up one night," says Yvonne Seon. "...getting a phone call saying “the Student Union is on fire” and my friend Ms. Jenkins and I drove up to the building all we could see was a blazing red on the horizon that looked like we’d had a sunset in the middle of the night, and this was at 3 o’clock in the morning."

The January 1969 fire, described by Seon, then Director of Student Life programs at Wilberforce University in Ohio, destroyed the Student Union. The building was a total loss estimated at $100,000. While arson was suspected, the cause of the fire remains unknown. For many, it seemed to be linked to black student unrest that had become common on many campuses by the late 1960s. These protests affected faculty and staff, as well as students. Dr. Ibram X. Kendi speaks about this movement in his book The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Racial Reconstitution of Higher Education, 1965- 1972.

"Most people are familiar with the fact that black students are really the ones who protested and demanded Black Studies," says Kendi. "That push for Black Studies was part of a larger movement, a larger social movement that I term the Black Campus Movement. I like to say that wherever there was a group of black students there was the Black Campus movement."

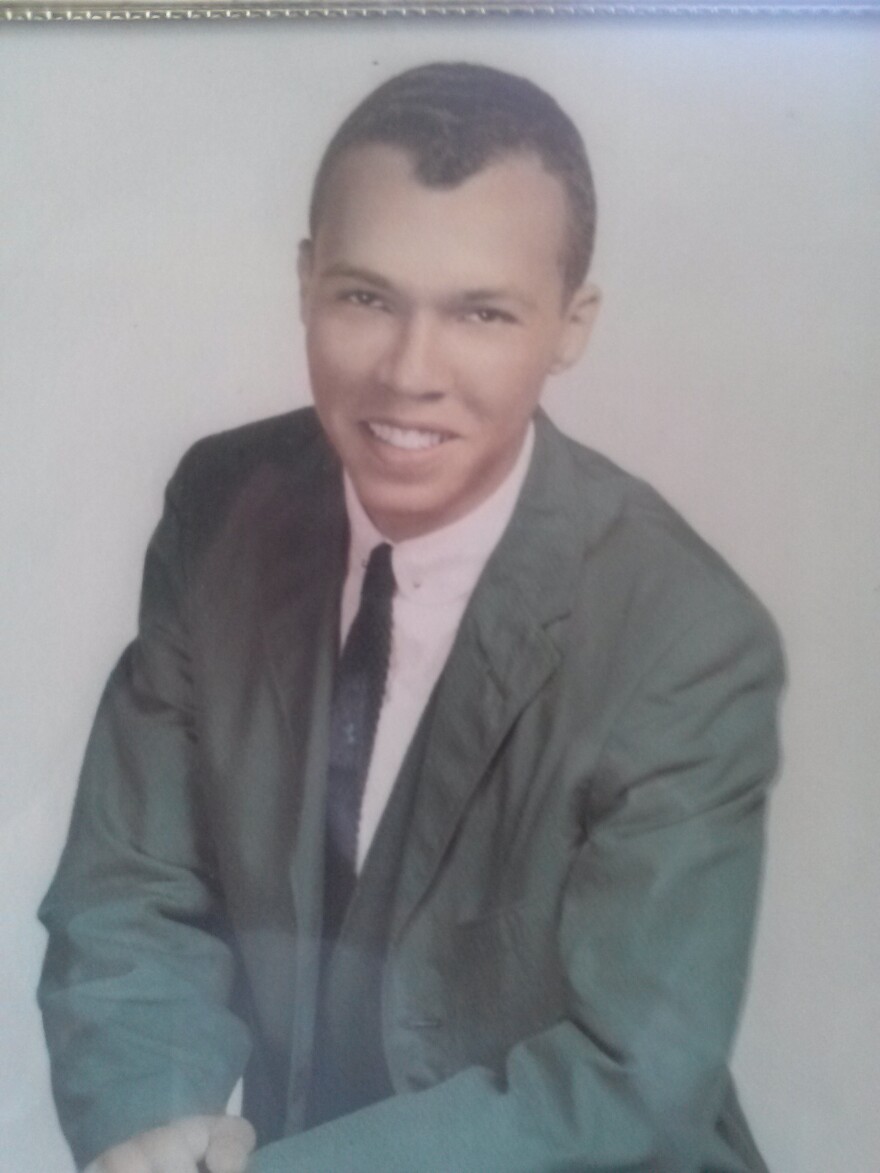

"Central State was probably… at that particular point everything was ultra-conservative," says Lee Robinson, a black graduate of Yellow Springs High School who attended Central State from 1961 to 1965. "I mean, they were more concerned seemingly in those days that the children… that’s how they referred to us in those days, is that they didn’t that the students didn’t disrespect the school or the elders, and Antioch seemed to be totally different. That was an interesting experience."

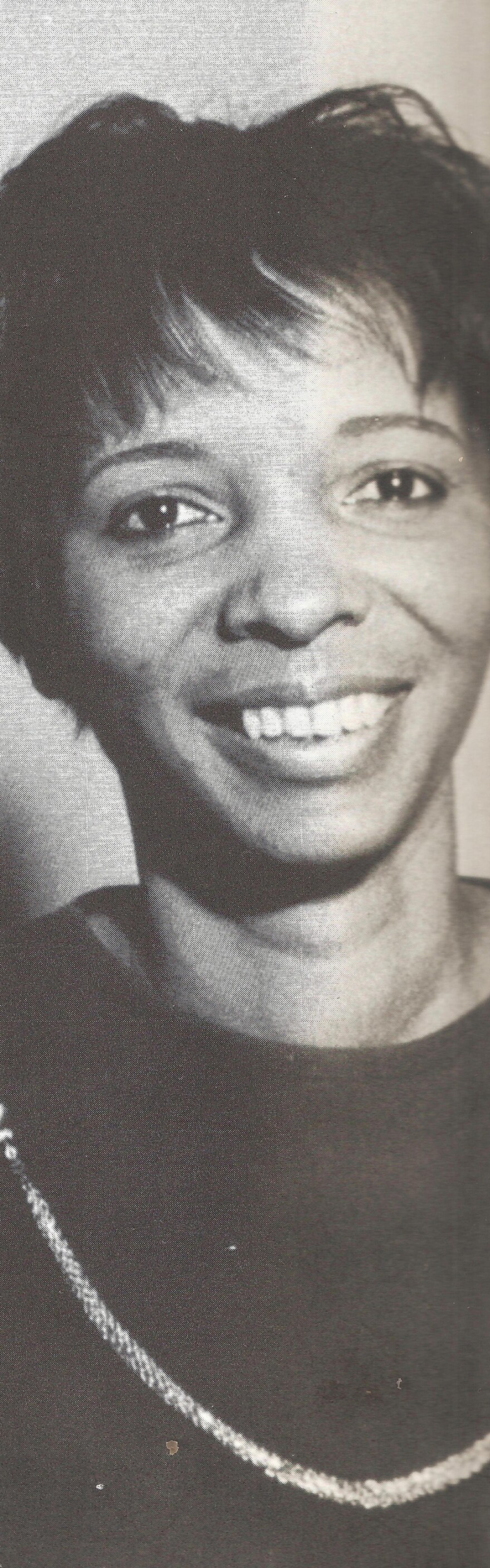

Alyce Earl Jenkins, who accompanied Yvonne Seon to view the burning Student Union at Wilbeforce was then Director of Counseling there and remembered student attitudes towards staff and faculty.

"The colleges, were affected by the students who all of the sudden saw the administrators and teachers and faculty members all of the sudden as being nothing but Uncle Toms, because they did not stand up for their rights— or we didn’t stand up for our rights, or we didn’t do the things that they felt we should be doing. So we had a lot of student unrest," says Jenkins.

Yvonne Seon described some of the student concerns at Wilberforce.

"College students at that time, everywhere, were becoming convinced that they could make a difference. They weren’t issues about what was going on in the world so much as about issues about campus life: the food isn’t well prepared. We need better meals. They wanted ambulance service in the event of something happening to them because they were so far from a hospital. That was the kind of thing that they were—those were the kinds of things—that was a part of the list of complaints that they presented to the President eventually."

Events such as the fire made for an extremely tense working environment. Aylce Earl Jenkins discussed her feelings following an incident in which students overran the counseling office with simultaneous requests for services.

"It was frightening to me. But it was-- more than that it was hurtful," says Alyce Earl Jenkins. "Because everybody was working so hard, especially at Wilberforce, they were working so hard to try to make sure they had a good education and all the resources they could possibly have. It—I mean it brought us to tears."

In 2012 when Wilberforce University students protested conditions on campus, they may not have been aware that were acting as part of a long tradition of protest on black campuses, protests that affected faculty and staff as well as students.